The pandemic has provided an ideal case study to illustrate market efficiency, puncture common myths and test various popular hypotheses.

Below are the top seven lessons from the crash that we believe are highly relevant for professional and private investors alike.

1. Do not try to predict the market.

The temptation to forecast economic cycles and market movements appears impervious to the overwhelming number of scientific studies showing the futility of attempting to make short-term market predictions. The COVID-19 crisis is a compelling case in point.

For the past few years, market commentators have been predicting the end of the bull market that began after the financial crisis in March 2009 and eventually ended in March 2020; a record 11-year run. Throughout this period, there have been hundreds of well-articulated research reports arguing that the bull market was long in the tooth and another crash must therefore be imminent. However, we can't recall a single report accurately predicting both the timing and cause, i.e. that markets would come crashing down in March 2020 due to a pandemic triggering unprecedented business interruption from a global lockdown. A crystal ball that does not accurately reveal both the timing and reason for a stock market crash is of limited use and may actually hurt rather than help investors, as further discussed below.

The standard warning to investors still very much applies: Avoid trying to time the market.

2. Cash is not king – stay fully invested.

Popular axioms such as "Cash is king" and "Keep some dry powder" imply that it is prudent to have cash available to deploy if the market pulls back to more attractive levels. The siren song with these lyrics usually grows louder when there is an episode of market panic. However, we disagree and believe that this notion, however well-intended, is more likely to harm rather than benefit long-term investors for two reasons.

First, in today's low interest rate environment, the return on cash is essentially zero. Investors with a long-term horizon who allocate a portion of their funds to cash implicitly choose to not be fully invested, thus foregoing a market return and (likely) incurring an opportunity cost. To that point, the global equity market, as represented by the MSCI AC World index, averaged more than 12% annual return (in USD) over the three years prior to the peak on 19 February. Any cash allocation during this period would have meant missing out on these stellar returns and the cumulative gains would likely have be significantly higher if the timeline were extended further. In fact, research from Bank of America shows the staggering opportunity cost of missing the best single days in the market. Since the 1930s, investors in the S&P 500 index who missed the ten best days each decade would have generated a total price return of 91%, compared to 14,962% for those who were fully invested.[1] The best days often follow the worst, when sentiment is depressed and it is easy for investors to mentally rationalise being out of the market.

Second, taking the decisive step to go against the flow and deploy cash when the market falls requires immense mental strength. It is this cognitive bias that the Nobel laureates Kahneman and Tversky refer to as loss aversion, i.e. that losses have a much larger psychological impact on investors than gains of similar size.[2] Investors need to overcome this bias to take full advantage of the magic of long-term compounding. Unfortunately, our experience is that both professional and private investors rarely step in with conviction when the opportunity presents itself. Given the unpredictable and forward-looking nature of the market, the recovery after a crash is often brisk and occurs well before the news headlines signal that the economy is on a sounder footing. How many investors who partially (or fully) sat out the stock market rally over the past few years while waiting for "a better entry point" actually rose to the occasion and deployed their cash at or around the market trough on 23 March?

In summary, we believe that investors hoarding cash risk losing at both ends. They are short-changed by missing the market rally before the crash and then typically fail to jump onboard amidst the panic, thus remaining on the sideline as the market swiftly returns to pre-crash highs.

Our advice to long-term investors who presumably believe that the market will rise over time: Stay fully invested.

3. Passive investing is not a bubble, at least not yet.

The active management industry has long complained that quantitative easing, ETF proliferation (passive indexing) and momentum strategies are distorting the equity market by suppressing volatility and increasing correlations, thus making it difficult for active managers to beat their benchmarks. A glimmer of hope appears every now and then with reports claiming that the time has come for "a stock picker's market", meaning that the environment is, or at least should be, particularly supportive for active managers to shine. The reasoning goes that a market with low volatility and high correlation between stocks offers limited prospects, whereas a volatile market is ripe with distinctive opportunities for stock pickers.

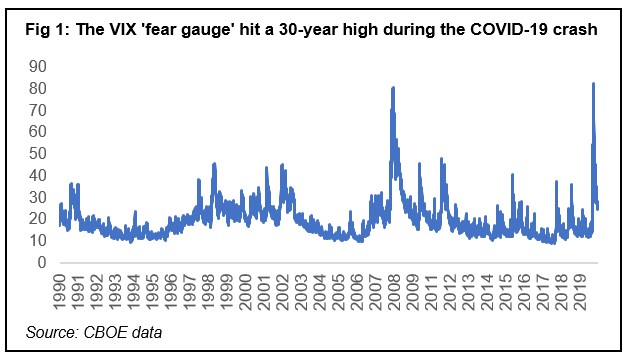

In this context, what can we learn from the COVID-19 induced crash? Considering that the VIX index – a measure of expected market volatility also known as the fear gauge – spiked to a 30-year high of 83 on 16 March (figure 1), you might think that the equity market during this turmoil would be a stock picker's paradise.[3] However, the raw data tells a different story. S&P Global, a financial information provider, reports that 66% of European equity fund managers underperformed their benchmark in March and 57% lagged over the first quarter.[4] Reviewing the track record of some 5,000 actively managed equity funds in Bloomberg's database, we find that over two thirds underperformed their respective benchmark during both time periods. Clearly, active managers (still) need to raise their game to stay alive and justify their existence.

Having passed this test during the coronavirus crash, passive investing looks set to continue its march towards market domination. However, every cloud has a silver lining. We note that roughly one third of active managers outperformed their benchmarks, sometimes by a considerable margin, and therefore may well offer investors a (much) better option than a plain vanilla index fund.

We encourage investors to not automatically default to passive indexing, but take a close look at active managers who have proven their worth.

4. Value stocks with low multiples are not defensive.

Over the past decade, a common mantra in some corners of the value investing community has been that beaten-down value stocks trading on low price-earnings or price-book metrics would be defensive because of the protection these depressed multiples provided. The COVID-19 crisis effectively punctured this hypothesis. Comparing the returns of the two major global equity style indices, MSCI AC World Growth and MSCI AC World Value, during the market downturn clearly illustrates this point. Between 12 February and 23 March, the former declined 30% while the latter fell 37%.

As we have previously explained in a white paper, the traditional definition of value investing has become obsolete in a world dominated by intangible assets that are inadequately captured by financial statements, due to outdated accounting principles. In fact, we would go so far as to state that the whole concept of "value investing" as typically described by industry data providers such as MSCI and Morningstar is due a complete overhaul to better reflect the world we live in today.

We continue to advocate a more dynamic "applied value investing" approach; an unconstrained investment style that draws on the wise words of the legendary American investor Charlie Munger: "All intelligent investing is value investing".

5. The belief that "dividends don't lie" is largely a chimera.

One of the most misunderstood concepts in the investment world is the role of dividends. A popular belief is that a high dividend yield signals a stock is undervalued and investors prioritise a high yield over total shareholder return (price appreciation plus dividend yield) when making long-term investment decisions. A related strategy that has come to enjoy widespread support among savers faced with essentially zero return on bank deposits is equity income investing, a purported low-risk equity investment alternative with the allure of a steady income stream, often buoyed by juicy dividend payments. Nothing could be further from the truth.

While it is true that reinvested dividends can make up a significant part of the total return in the long run, a key assumption is that the dividend is both sustainable and sizeable. Unfortunately, a high dividend yield often represents forbidden fruit and the temptation to pocket a large near-term gain blinds many investors from the flashing red lights signaling trouble ahead.

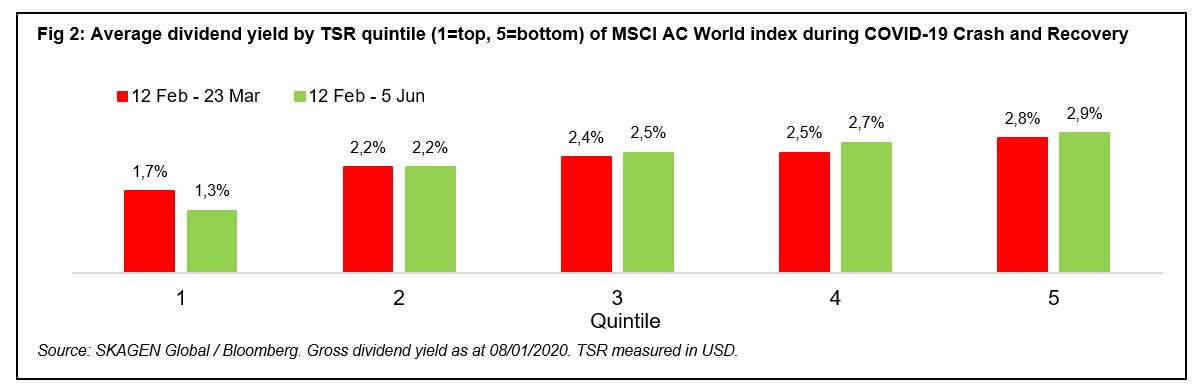

Indeed, those who piled into stocks with high dividend yields at the beginning of the year have taken blows from several different angles. Figure 2 shows that the quintile of worst performing stocks in the MSCI AC World index based on total shareholder return (TSR) during the market panic (red bars) also had the highest average dividend yield.[5] When including the recovery phase in the performance assessment (green bars) the bottom quintile similarly contained those with the highest average dividend yield.[6],[7]

Many companies with high dividend yields were on shaky ground with unhealthy payout ratios and deteriorating fundamentals even prior to the virus hit. The economic wreckage in the wake of the coronavirus may have been the final nail in the coffin for those overdistributing relative to their true earnings power, forcing a steep dividend cut often with a concomitant share price fall.

Other companies have seen their share price suffer due to regulatory intervention prohibiting dividend distribution. This is especially true in the financial sector where dividends often play an equal, if not greater, role than earnings growth in shareholder return. One could argue that the extraordinary action by regulators to limit payouts may lead to a permanently higher equity risk premium for the sector, a development that would make a swift share price recovery less likely. In some sense the epidemic was merely a catalyst for exposing unsustainable dividend practices and thus accelerating the inevitable outcome.

Our unequivocal message to dividend investors: Focus on total return to maximise long-term gains; dividends do not tell the whole truth and can be deceptive.

6. Technology merits attention, not disdain.

Whether the so-called FAANG stocks, as a group or a proxy for the broader technology sector, represent an overvalued part of the equity market has been subject to much debate.[8] Numerous articles have predicted that the FAANG bubble would pop at the next downturn. Interestingly, the technology space has been anything but fragile during the COVID-19 downdraft. All five FAANGs and the Information Technology sector as a whole outperformed the MSCI AC World index during the COVID-19 downdraft. Moreover, one could even argue that the digital economy took a big leap forward by exposing new broad segments of consumers to its emergence.

The COVID-19 crisis also made clear how entrenched technology has become in everyday life. The Silicon Valley giants and their smaller cousins certainly illicit envy and contempt as they disrupt one industry after another, but consumers across the globe largely embrace the convenience offered by their products. Indeed, life without internet content, electronic payments and online shopping is beginning to seem inconceivable. We surmise that it would take material economic hardship before consumers would cut out spending on these items, prompting the question whether some of these technology companies are becoming the new consumer staples stocks with resilient earnings and growing cash flows?

Importantly, as bottom-up investors we recognise that no trees reach the sky and every company needs to be fundamentally assessed in isolation - not as part of an arbitrary acronym. Still, dismissing the tech giants as a bubble strikes us as providing an overly simplistic answer to a complex question that merits an in-depth review on an individual company basis.

We don’t claim to have all the answers but believe investors would be well served to ask themselves what role technology will play in our lives in ten years' time and then consider what the investment implications will be.

7. Do not naively dismiss the market as irrational.

It is popular to blame the market for being irrational and increasingly driven by "dumb ETF flows", trend-following algorithms and other short-term oriented trading strategies. However, we believe the market forcefully dispelled these accusations during the COVID-19 crisis by being the most reliable indicator of where the world was heading - both on the way down and up. Amid the flurry of reported infections, debates and dogmas in the avalanche of news, the market seems to have been one of the few actors that succeeded in keeping its cool. The proverbial wisdom of the crowd skillfully drew conclusions about the virus and its future economic implications. For example, by the time California became the first US state to impose a strict stay-at-home order, the global equity market had already fallen 30% in the preceding month.

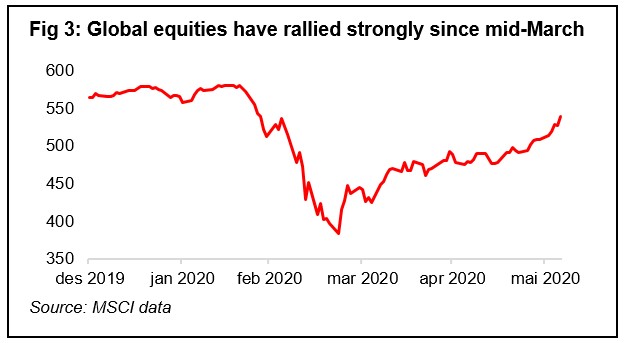

Similarly, the market appears to have realised that the economic recovery is likely to be faster than commonly perceived. While only 15% of the respondents in Bank of America's Global Fund Manager survey in April (and 10% in May) believed in a V-shaped recovery, the MSCI AC World index staged an impressive comeback and rallied 34% between 19 March and 5 June (figure 3).[9] It is easy to forget that markets are forward-looking and there is typically a lag until the media catches up with the stock market. We believe this point is often lost in the heat of the moment, as seen in recent weeks with market participants stubbornly clinging to the view that there must be a disconnect between the market rally and economic reality. The jury is still out whether the market or the survey-responding fund managers will ultimately be correct but, if forced, we would place our bets on the market.

Our recommendation is straight-forward: Do not automatically assume that the market is irrational, rather try to think what the market movements may be signaling about the future.

Conclusion

Each crisis naturally has winners and losers and the COVID-19 pandemic is not unique in this regard. Who would have guessed in early January that the world's largest manufacturer of rubber gloves and a video communication platform would be among the top-5 performers in the global index five months later?[10] Such data points make good headlines but in reality offer little by way of insight for future investment success. Therefore, long-term investors should analyse recent events with a view to identifying the important lessons that illustrate investment principles likely to drive significant wealth creation until, during and beyond the next crisis. Won't it soon be time to start predicting when and how it will strike?

Footnotes

[1] Subramanian, Savita. Bank of America. The end of the longest bull market ever. Now what? 13 March 2020

[2] Kahneman, D., and Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47, 263–291. doi: 10.2307/1914185

[3] Chicago Board Options Exchange Volatility Index

[4] https://www.spglobal.com/en/research-insights/articles/no-immunity-for-active-managers

[5] SKAGEN Global / Bloomberg. Gross dividend yield on 8 January 2020 as reported by Bloomberg. TSR measured in USD

[6] SKAGEN Global / Bloomberg. Gross dividend yield on 8 January 2020 as reported by Bloomberg. TSR measured in USD

[7] Using median rather than average dividend yield per quintile does not change the overall result significantly

[8] FAANG = Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, Google

[9] Michael Hartnett, Bank of America. Global Fund Manager Survey, 14 April 2020 / 19 May 2020

[10] Top Glove Corporation, Zoom Video Communications